Fate of Britain post Brexit

- Finomenon NMIMS

- Aug 16, 2019

- 7 min read

It is a word that is used as a shorthand way of saying the UK leaving the European Union - merging the words Britain and exit to get Brexit, in the same way as a possible Greek exit from the euro was dubbed Grexit in the past.

The European Union - often known as the EU - is an economic and political partnership involving 28 European countries. It began after World War Two to foster economic co-operation, with the idea that countries which trade together were more likely to avoid going to war with each other. It has since grown to become a "single market" allowing goods and people to move around, basically as if the member states were one country. It has its own currency, the euro, which is used by 19 of the member countries, its own parliament and it now sets rules in a wide range of areas - including on the environment, transport, consumer rights and even things such as mobile phone charges.

There can be two types of Brexits -

Brexit with Deal

No-Deal Brexit

If there is a deal with the EU?

Under the plan EU citizens legally resident in the UK and UK citizens in the EU will be able to leave for up to five years before losing the rights they will have as part of the proposed Brexit deal.

Under the Brexit deal, EU citizens and UK nationals will continue to be able to travel freely with a passport or identity card until the end of the transition period

Passport is a British document - there is no such thing as an EU passport, so the passport will stay the same. The government has decided to change the color to blue for anyone applying for a new or replacement British passport

If there is a no-deal Brexit?

The value of the UK’s currency – which floats freely against other countries’ currencies – is a measure of the country’s economic strength and stability, although currency values are affected by numerous other factors. The deterioration of sterling since the Brexit vote is, to an extent, an indication that the vote caused market participants to take a more negative view of the UK’s economic strength – in other words, it is a direct reflection of the majority view among economists that Brexit will reduce economic growth

Without a trade agreement, ports would be blocked and airlines grounded. In no time, imported food and drugs would run short.

U.K. would no longer be a member of the EU and it would have no trade agreement. It would eliminate Britain's tariff-free trade status with the other EU members. Tariffs would raise the cost of exports. That would hurt exporters as their goods became higher-priced in Europe. Some of that pain would be offset by a weaker pound.

Tariffs would also increase prices of imports into the U.K. One-third of its food comes from the EU.

Northern Ireland would remain with the United Kingdom. The country of Ireland, with which it shares a border, would stay a part of the EU. Johnson's plan would create a customs border between the two Irish countries

A hard Brexit would hurt Britain's younger workers. Germany is projected to have a labor shortage of 2 million workers by 2030. Those jobs will no longer be as readily available to the U.K.'s workers after Brexit.

London has already lost many nurses and other health care professionals. In the year following the referendum, almost 10,000 of them quit. The number of nurses from Europe registering to practice in Britain has dropped by almost 90%.

Economic implications of Brexit

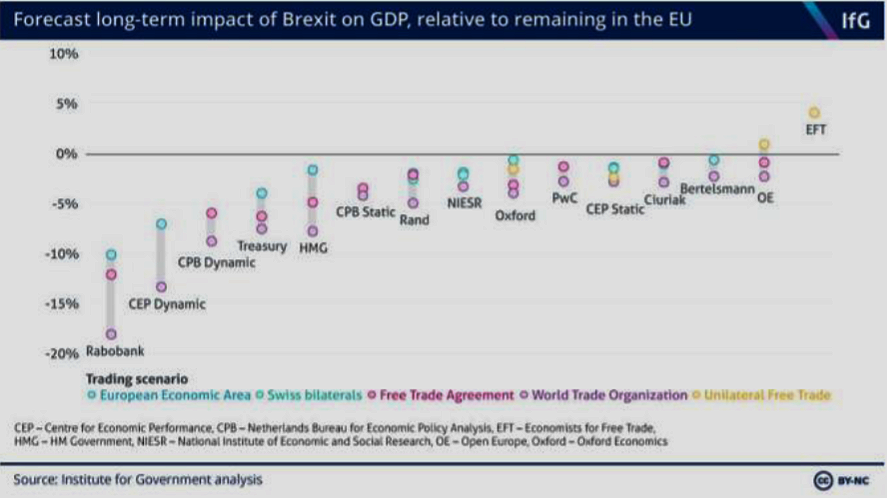

There have been numerous analysis by many institutions and the government itself on the economic impacts of all the various possibilities of a Brexit (deal or no-deal and everything in between). The chosen trade arrangement will largely depend on the UK’s negotiations with the EU. This will involve a complex set of talks between both parties involving multiple issues. The Brexit negotiations appear to be particularly challenging for the UK, as it attempts to disentangle its current ties with the EU while also negotiating arrangements for a future UK–EU trading relationship. However, a range of different trade opportunities and arrangements are possible between the UK and European Union (EU), and other countries, such as the United States, post-Brexit. Most of the analysis show that the UK will be economically worse-off outside of the EU under most plausible scenarios. The key question for the UK is how much worse-off it will be post-Brexit. In one study conducted by the Oxford University, among all the possible scenarios of a Brexit, the best-case scenario would result in a 0.1% loss in GDP by 2030 whereas a worst-case scenario would result in a 3.9% loss in GDP by 2030.

In another study by the RAND Corporation, the option of leaving the EU with no deal and simply applying World Trade Organization (WTO) rules would lead to the greatest economic losses for the UK. The analysis of this particular scenario shows that trading under WTO rules would reduce future GDP by around five per cent ten years after Brexit, or $140 billion, compared with EU membership.

The WTO outcome would likely move the UK decisively away from EU standards and result in significantly increased non-tariff standards, harming the ability of UK businesses to sell services to EU countries. The services sector, including financial services, dominates the UK economy, contributing to around 80 per cent of its GDP. It has been suggested that under WTO rules, the EU would also lose out economically, but nowhere near the same proportion as the UK. The economic loss to the EU could be about 0.7 per cent of its overall GDP ten years after Brexit.

For the most part, varying assumptions in different studies, in particular the different assumptions made about the following five areas - rather than different economic models – drive the varying predictions of each study:

Trade barriers can be reduced either by removing tariffs or eliminating non-tariff barriers to trade. Historic evidence on trade in goods and services strongly supports the notion that barriers to trade reduce trade between countries and thus reduce economic output. Numerous academic studies find this. All the projections made for the impact of Brexit on the UK economy assume this relationship holds. Indeed, the main way in which economists think Brexit will affect UK economic growth is through its potential impact on barriers to trade. But studies differ in what they assume about exactly what will happen to non-tariff barriers between the UK, the EU and non-EU countries and exactly how these would affect growth.

Foreign Direct Investment contributes directly to national income, providing firms with additional funds to invest in expanding their businesses. It can also help raise productivity by giving companies access to new ideas from abroad. About two fifths (42.6%, as of January 2018) of foreign investment in the UK comes from other EU countries. Theory and empirical evidence suggests that the UK’s attractiveness to foreign investors is closely tied to trade – that is, the ability of multinational companies based in the UK to be part of global supply chains and to serve a larger market beyond the UK’s shores. Leaving the EU could, therefore, affect the UK’s attractiveness to foreign investors.

Migration – from the EU and elsewhere – after Brexit could also have important effects on long-term economic growth. Most studies have shown that different assumptions about future changes to the rules governing the migration of skilled and unskilled workers can have as significant a direct impact on overall economic growth as trade. Migration affects overall economic output by changing the number of workers, changing the mix of skills available and potentially by affecting levels of innovation within an economy

Regulations affect how cost-effectively businesses are able to use workers, capital and technology to produce output. But regulations also have a purpose, aiming to ensure that certain objectives – for example, around competition, health and safety or 7 environmental protection – are achieved. Some studies suggest significant economic gains if the UK repealed or adapted regulation as a result of leaving EU.

Productivity in the long term is crucial for economic growth. Becoming more productive means that workers can produce increasingly large quantities of output without needing any more capital to work with. This is key to enabling rising living standards. Economists do not have a good understanding of why UK productivity growth has been so poor in recent years and so it is difficult to predict with any certainty how it might change in future. Economic theory suggests that trade can boost productivity but the size of this effect is difficult to estimate and the empirical evidence on this question is mixed. If Brexit has a permanent impact on productivity growth, it would have a large effect on the UK’s future growth.

The studies of the economic impact of Brexit broadly attempt to predict how much larger or smaller the UK economy will be in 2030 – that is, once the UK and EU have adjusted to a new relationship with one another. The short-term economic impact could either be significantly more disruptive than the long-term projections suggest or less so, depending on how the negotiations play out.

If the UK Parliament supports the agreement reached between the UK government and the EU and if both sides make good progress in implementing the new systems needed to facilitate the future trading relationship, the short-term impact could be much smaller than the long-term effects predicted.

But if no agreement can be reached that is acceptable to both the counter parties, then the short-term economic impact could be much more severe than the predictions for a long-term WTO-based relationship suggest. Overall, it is in the best interests of the UK, and to a lesser extent the EU, to work together to achieve some sort of open trading and investment relationship post-Brexit. The “no deal/WTO rules” option would be economically damaging to both parties.

Comments